I’ve been unusually studious this summer, actually focusing on paring down my reading list (partly out of jealousy after learning that my little sister read 40 BOOKS LAST YEAR WHAT THE ACTUAL CHEESEBALLS ANNIE). At some point I should probably do a bragging “this is what I’ve been reading” post, but before I do that, I wanted to do one specifically dedicated on a book VERY different from the sort I usually read, namely, The Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant.

Nonfiction is usually not my thing. There aren’t enough dragons and laser swords in them. I can’t even claim to have particular interest in the American Civil War, or at least, I couldn’t until Youtube started recommending clips of the 1990 movie “Gettysburg” to me, and History Channel’s miniseries Grant, which chiefly is what reawakened my interest in this remarkable figure in American history.

I grew up quite confident that Grant had been just a drunken idiot who had worn down the South by virtue of numbers and merciless warfare. I can’t recall any specific teacher who told me this, or even gave this impression–I mostly remember picking it up from fellow classmates and op-ed pieces. Even in college, though, which was where I was confronted with the massive amount of confederate speeches and constitutions proclaiming that they totally were fighting for slavery and not states rights, I didn’t receive much to counter this idea of Grant as a sub-par commander, the American History professor being more interested in the ideological underpinnings of the war and not the military way it played out.

The miniseries Grant presents him as a much more capable general, but was more interesting to me was how it presented Grant as a man of conscience. A newly-radicalized Christian Nationalist friend of mine had argued with me recently over Grant owning slaves while a farmer (something Grant does not mention in his memoir), but the miniseries points out that Grant was given his slaves by his father-in-law, and freed them after two years of ownership, instead of selling them for what would have been at the time a years worth of wages. It also mentioned his memoir, and that Grant wrote it while under great pain from throat and lung cancer.

“Man,” I thought, “That must have been interesting reading. I wish I was around then, so I could read it.”

And then my brain actually kicked in and realized, everything from the 1890’s backward is in the public domain, Grant’s memoir is probably just sitting on the internet somewhere, living history, waiting for you to read it. The thought made me a little ashamed, actually. Turns out nearly every general involved in the Civil War wrote their own independent recollections of it, and they’re all available online, some in audiobook form. Practically anybody could be a Civil War scholar if they wanted to be.

To be clear, I’m not sure if I want to be. But Grant’s memoir (I ended up reading an annotated version I picked up from the local library) did make for fascinating reading. The language was fairly simple and easy to follow, though at times it was hard to keep all the locations and generals straight. And it was, really, quite surprising in a number of ways.

Grant was Not a Natural Soldier

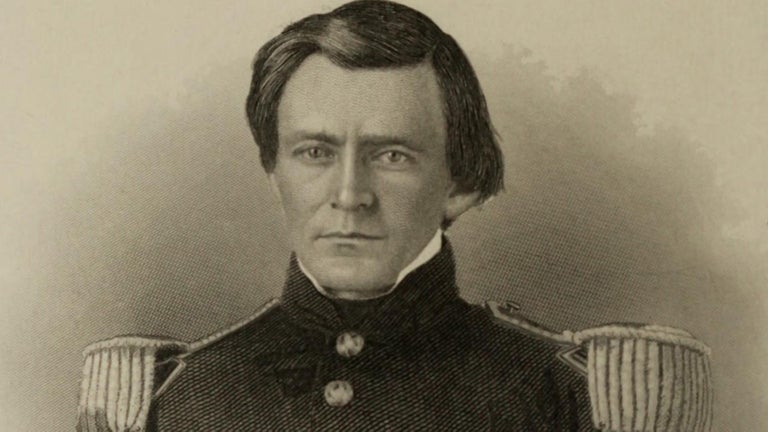

Hiram Ulysses Grant (He became known as Ulysses S due to an error on enrolling in Westpoint) never wanted to be a soldier. His father sent in the application, and when Hiram said he didn’t think he would make a good soldier, his father said he thought he would, and that should be good enough for him. Grant had very poor grades at West Point, but thought of becoming a lecturer and making an income at that.

The Mexican-American War interrupted those plans. Grant felt very strongly that the Mexican-American war was unjust. He writes at length about how the Texan treaty with Santa Anna was obtained from him under duress (They would have been right to kill him, Grant argues, but they should have just done that instead of obtaining a peace treaty), and that the politicians in Washington did everything in their power to provoke what he saw as a land-grab war with Mexico.

“For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory” (Chptr III).

He suspected that the commanding general Zachary Taylor disapproved of it also, though he had little interaction with Taylor and that was but supposition. He ends, though, by saying:

“The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times” (Chptr III).

Grant believed that the Civil War was a direct result of the Mexican American War., a sort of divine retribution. He seems to think that the whole process of settling Texas and then seceding from Mexico was part of a plot by the slave states to increase their power in Washington, but even independent of that, thinks that the political machinations used to claim territory all the way to California was the worst sort of European-style land-grabbing.

Even once the Civil War hits, Grant is not particularly eager to sign up, and when he finds himself actually a colonel in command leading his troops into what he thought would be his first engagement, he is dreadfully terrified of doing something wrong.

My sensations as we approached what I supposed might be “a field of battle” were anything but agreeable. I had been in all the engagements in Mexico that it was possible for one person to be in; but not in command. If some one else had been colonel and I had been lieutenant-colonel I do not think I would have felt any trepidation. (Chptr XVIII)

The scene ends in comedy, though, as Grant approaches, heart in mouth, only to find that his Confederate opponent had already fled the field.

“It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards…. The lesson was valuable” (Chptr XVIII).

So What Made Him So Special?

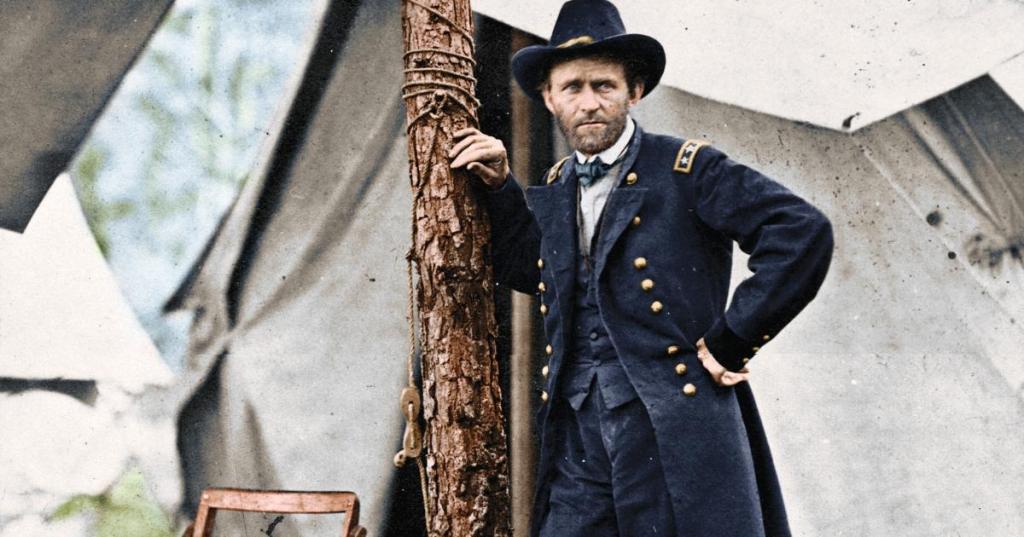

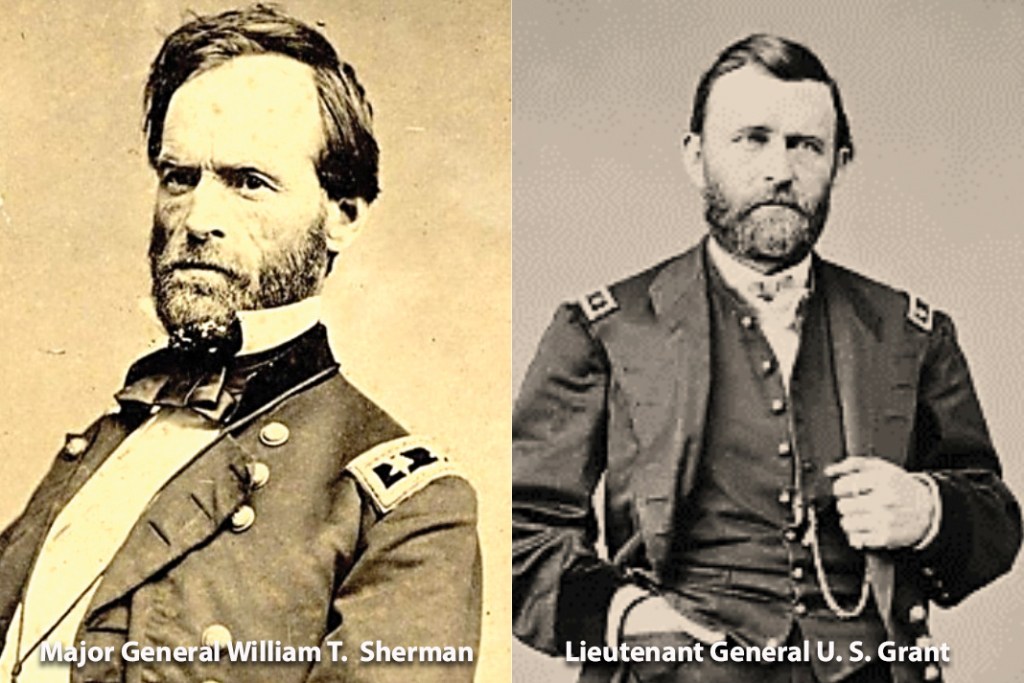

Grant does not come off, even in his own memoir, as a particular military genius. He frankly admits mistakes and sometimes says various tactics were tried simply to see what would happen. But the early story of him facing off against Harris and realizing Harris was scared of him does illustrate a noted advantage of Grant’s over the other Union generals–to quote Lincoln: “He fights.” William T. Sherman is famous for candidly saying that he considered himself a smarter general than Grant, but that Grant did not distract himself by constantly worrying what the enemy might do or go.

It’s not entirely true, as the memoirs show Grant did often think about likely Confederate actions, but Grant always carried in mind that the Rebels were just as scared as them.

Another explanation for Grant’s aggressive drive perhaps, can be gleaned from Grant noting: “One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go any where, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished.” (Chptr III). Just on a tempermental level, Grant was a go-getter who didn’t like waiting around.

But there is I think also an ideological edge that Grant had. Grant, I believe was a stronger anti-slavery crusader than he’s given credit for. His father was an abolitionist, he (briefly) was acquainted with John Brown, and while he married into a slaveholding family, he clearly despised the trade. He wanted the war to be won, he wanted slavery to be crushed. While president, he met with German Chancellor Otto Von Bismark and had this to say about the war.

“You are so happily placed in America that you need fear no wars,” said Bismarck, who ruled a country that bordered its rivals. “What always seemed so sad to me about your last great war was that you were fighting your own people. That is always so terrible in wars, so hard.”

“But it had to be done,” Grant replied.

“Yes,” said Bismarck. “You had to save the Union just as we had to save Germany.”

“Not only save the Union,” said Grant, “but destroy slavery.”

“I suppose, however, the Union was the real sentiment, the dominant sentiment,“ said Bismarck. ….

“As soon as slavery fired up the flag, it was felt—we all felt, even those who did not object to slaves— that slavery must be destroyed,” Grant explained. “We felt that it was a stain on the Union that men should be bought and sold like cattle… There had to be an end of slavery. Then we were fighting an enemy with whom we could not make a peace. We had to destroy him. No convention, no treaty, was possible—only destruction.”

In his memoir, he says something similar:

There was no time during the rebellion when I did not think, and often say, that the South was more to be benefited by its defeat than the North. The latter had the people, the institutions, and the territory to make a great and prosperous nation. The former was burdened with an institution abhorrent to all civilized people not brought up under it, and one which degraded labor, kept it in ignorance, and enervated the governing class. With the outside world at war with this institution, they could not have extended their territory. The labor of the country was not skilled, nor allowed to become so. The whites could not toil without becoming degraded, and those who did were denominated “poor white trash.” The system of labor would have soon exhausted the soil and left the people poor. The non-slaveholders would have left the country, and the small slaveholder must have sold out to his more fortunate neighbor. Soon the slaves would have outnumbered the masters, and, not being in sympathy with them, would have risen in their might and exterminated them. The war was expensive to the South as well as to the North, both in blood and treasure, but it was worth all it cost. (Chptr XLI)

He views it as a good thing for the South that slavery was crushed, as neither America nor the South could have been considered “civilized” while they continued to enslave human beings, after the rest of the world had outlawed the trade. (It’s worth noting that Grant also does not come across as a racial egalitarian–he argues that “social equality was never thought of” before the war, and seems to view the granting of the vote to former slaves as a necessary evil.)

Certainly, though, Grant felt slavery should be abolished, and I think that gave him a commitment to the war that others lacked. From the very first moments of the war, Grant, even as an indifferent Colonel, has a vision for how the South can be crushed, which is what leads him to make the initial plans to attack Forts Henry and Donelson. When Sherman argues against the campaign at Vicksburg, Grant’s answer is that retreating will cause disaster for the pro-war politicians in the upcoming elections, and if they lose than the Federals will sue for peace and the cause be lost. While other Union generals may have disapproved of slavery generally, Grant had an understated righteous passion against it that I think pushed him keep going at a rate other generals considered hazardous.

One final point: A crucial tactic, possibly controversial, that also gave Grant an edge over Union generals, was his willingness to pillage supplies from the surrounding Southerners. Standard military doctrine held it was extremely important to stabilize your supply lines before going into enemy territory. Other Union generals like Burnside and Thomas would spend a great deal of time setting up a firm route of supply before venturing into Rebel territory. Sherman,even, argued with Grant about this very point before Vicksburg. Grant, however, realized quickly that the rural South held all sorts of supplies readily available around them, which would be used to support the Rebels if the federals did not seize them. The Vicksburg campaign convinced Sherman that Grant was absolutely right, providing the blueprint for Sherman’s own infamous “March to the Sea.” (Grant’s opinion as expressed in his memoirs was that Sherman’s march was necessary and the crimes overblown).

I’m frankly not sure how to feel about this “tactic” of Grant’s. He insists that he always gave the owners payment for their goods and ordered his troops not to molest the Southerners otherwise. He also argues that the South was all-in on the war effort, to the point that any “civilians” were likely supplying and informing the Rebel army. He compares it to a large military camp run by a military dictatorship. Still, it likely fed into bad feeling against the North that made Reconstruction harder.

Grant’s Attitude Toward Rebels

Grant was known as “Unconditional Surrender Grant” in the press, and what also comes out in his memoirs is how this is rooted in his deep and abiding disgust toward the Confederate government. He points out that the North still had elections and free press, while in the South anyone who even spoke in favor of the Union was summarily hung without a trial. He also points out that the South claimed some border states like Tennessee and Missouri, even though the state legislatures had voted against secession. To him, they are no-good rebels who seized power and deliberately started the war by firing on a federal fort they had no right to.

At the same time Grant is remarkably able to hold two competing views of a person. He often mentions how he was happy to let Confederate prisoners slip away, since he guessed most would return to their farms and homes and never join the Confederate cause again. Most notably, Nathan Bedford Forrest (founder of the KKK, though Grant may not have known this), he describes whenever he refers to him as “a gallant and capable calvary officer,” but when Forrest captures Fort Pillow, a backwoods garrison staffed entirely by a colored regiment, Grant acidly notes:

I will leave Forrest in his dispatches to tell what he did with them. “The river was dyed,” he says, “with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed, but few of the officers escaping. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.” Subsequently Forrest made a report in which he left out the part which shocks humanity to read. (Chptr XVLII)

So Grant respects the fighting abilities of the Confederates, but at the same time he clearly strongly disapproves of their methods and their motivations. He empathizes with some of them as human beings, but that doesn’t make them any less wrong, or in some case, any less actually horrific. It certainly doesn’t make their government any less wrong.

Problems with His Own Side

One particularly surprising point to me, reading, was how often Grant’s own soldiers, actually, refused orders. I’ve never been in the army, but I’ve always had this assumption that it operates on a “theirs but to do and die” mentality. Indeed, I’d say one of the biggest examples of this comes from the Civil War, i.e. Pickett’s Charge, which General Longstreet allegedly could scarcely bring himself to issue the orders for because of how terrible an idea he knew it was.

But Grant notes a number of incidents where he gives explicit orders to another general to launch a campaign–often a vitally important one–and soon finds that the other general has not launched. The worst example of this is when he tries to dispatch Granger to the relief of Burnside after the battle of Chattanooga. Though Grant is officially in charge of all the forces at Chattanooga, and even though Grant has, personally, overseen all the preparations to send out Granger the minute Missionary Ridge is taken, and even though Burnside is in very dire straits and in need of relief, Grant returns several days later to Chattanooga to find that Granger is still there and has not taken advantage of the steamers prepared. “Finding that Granger had not only not started but was very reluctant to go, he having decided for himself that it was a very bad move to make, I sent word to General Sherman of the situation and directed him to march to the relief of Knoxville” (Chptr XLV). I didn’t know that was an option in the army. Just… you decide it’s a bad order and that you’re not going to follow it? There must have been some other point going on here, because Grant doesn’t mention any disciplinary action after. Wikipedia is also unhelpful, simply describing Granger as uniformly awesome and merely remarking that Grant “took a dislike to him” which seems understandable.

Another way Grant was hobbled was the way the secretary of war, Stanton, tried to micromanage things. Grant approvingly notes the way telegraphs could be set up to run directly into his tent, so that he could immediately communicate with forces in Atlanta and Shenandoah. The only problem is that these messages first went to Washington, where occasionally Stanton and the Chief of the Army, General Halleck, would alter them to what they felt Grant’s priorities should be. Grant notes one time that the message was so altered that the receiving general, Sheridan, sent back a protest telegram saying that the orders would hurt their position and that he would sooner resign. Grant ended up sending a runner with his true orders. Another time, Grant left his position in Virginia to meet with the Sheridan privately, specifically because he knew that Halleck and Stanton would disapprove of his idea and would, as before, change the order without saying so.

The added hurdle that Grant had to undergo to achieve results underscores all the more the challenges he was under, and the corresponding triumph of his achievement.

Conclusion

I’m not, of course, a Civil War historian by any means, though I am curious to peak at at least a few more memoirs–Joshua Chamberlain of Little Round Top, for instance, or Gen. Buford who held the line at Gettysburg. There’s also, apparently, a book out there that argues an underappreciated aspect of the war was the North’s fear that France (which had recently staged a coup in Mexico) or some other European power would ally with the South and use them as a means to stage a takeover of the bulk of the United States. That sounds interesting, and something I’d like to hear more about. But for right now, I’m content having learned a great deal more about this fascinating American figure.

One thought on “On the Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant”