I’ve mentioned or hinted a few times that my upbringing was a trifle unique. (Reading this a second time, I realize that sounds like I was part of a cult. That’s not what this is) For instance, the school I attended growing up was an independent private Christian school that my parents had helped to found. As a result, I received a uniquely comprehensive religious education, which among other things, included a highly interesting class called “Cults and World Religions”, which I recall taking my junior year of high school.

Strictly speaking, it wasn’t the most useful class, as I haven’t had opportunity to put my wide breadth of knowledge about Freemasons or Scientologists to any practical purpose. I haven’t even met any Christian Science adherents, and while it’s been fun to know the more bizarre points of Mormon eschatology and the sordid history behind the phrase “drink the Kool-aid” in relation to the infamous Jim Jones cult, I’ve only met vanishingly few cultists (who would have probably been deeply offended to learn I considered them a “cult”). Indeed, one under-rated point I’ve since learned to be more careful of is what even distinguishes a “cult” from a “religion.” My teacher at the time said it was a group that claimed to be Christian but differed from Christianity on several key points of unity like Christ being the son of God, etc. This is not, needless to say, a definition that everyone agrees on.

However, while the class wasn’t “useful” in the strictest sense, it was, certainly, deeply fascinating–indeed, I’d say it was probably the class I remember the most from in my high school experience. The compelling thing is, I’d say that that fascination–the glee and power-trip of knowing more than others, knowing about obscure, maybe even sordid details that others don’t know–is similarly at the heart of a lot of cult-like groups.

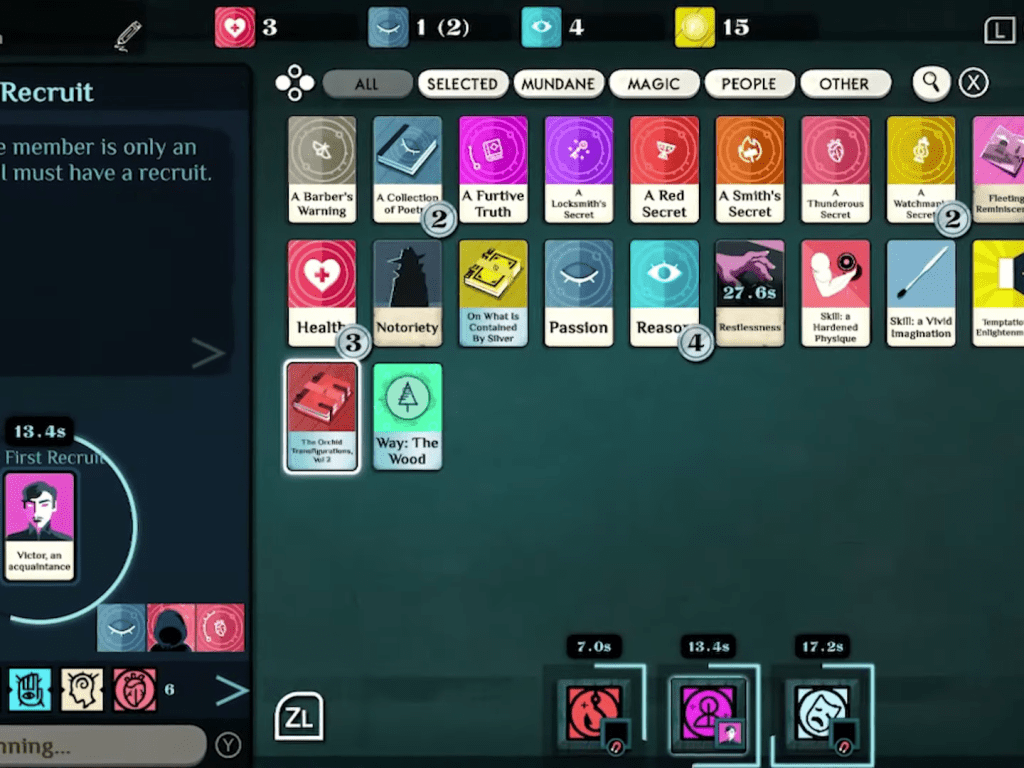

What got me thinking about this was the game Book of Hours, which I mentioned in my recent Steam Gems recommendations post. It’s made, as I said there, by the same people who made Cultist Simulator, a gaming company called Weather Factory. Despite the sordid title, Cultist Simulator is remarkably drab in its presentation–it’s literally just a series of minimally designed cards with odd titles that you allocate to various slots to help you acquire knowledge, spiritualism, followers, and even basics like money and power (the easiest way to lose Cultist Simulator is to have a bad job and die from not being able to afford basic necessities).

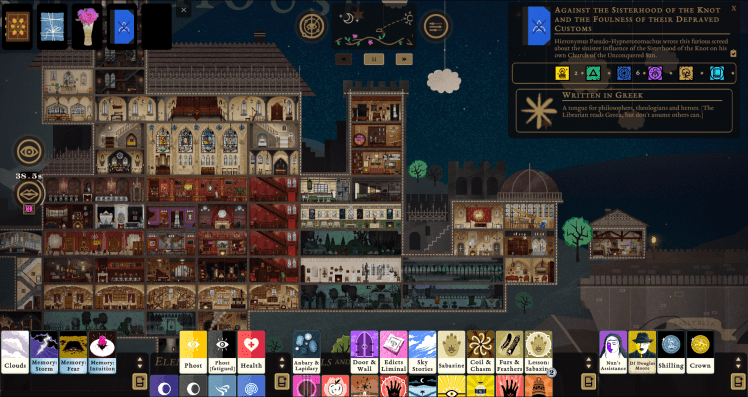

Despite this, Cultist Simulator is a very engaging game, and the reason why hit me as I was playing the follow-up, Book of Hours. Like its forebear, the core mechanic is allocating cards into slots, but here you’re given the tangible goal (in addition to expanding knowledge and spiritualism) of exploring a haunted library and cataloguing its books. The gameplay is a lot more forgiving than Cultist, the environments a lot more colorful. And I, as a former academic who enjoys reading, reflected that the game had hit marvelously on one of the central joys of reading–the ability to acquire, grow, and develop knowledge in a way that helps you understand the world around you.

But that wasn’t it, I realized. Both games were appealing because they had hit on the wonderful appeal of knowing “secret” knowledge–even knowledge that was functionally useless, outside of the fantasy world of the game. In the game, reading the books of Hush House can help you solve secrets, open paths, reveal new treasures–or horrors. They make you sought out by strange and diverse associates of influence and power. Outside the game, of course, knowing the secrets of DeWulf Barony and their hidden seer, or the fabulous histories of the pre-human Carapace Cross, are utterly pointless and of no value to anyone. But within the game, it makes you powerful and respected. And of course, there is an independent element of the joy of discovery, helped by the amazing artwork and writing in the game.

It’s the same delight, I think, that ensnares some people so heavily in cults (or cult-like) groups. You’re among an elite few who know that the Native Americans are the lost thirteenth tribe of Israel, or that there’s a flying saucer behind the Hale-Bopp comet. You are, in some cases, legitimately the member of a secret Space Navy.

“Cult” of course, is an oft-disputed term, but in a way it’s not even needed here, because the same phenomenon holds over groups we wouldn’t consider cults. Dr. Paul R. McHugh, a respected psychiatrist at John Hopkins medicine, notes archly in his book The Mind Has Mountains about the persistent appeal of “manneristic” Freudism.

…the explosion of interest in repressed memories was… a notion born from the Freudian movement’s death throes… the situation faced by therapists accustomed for so long to remarkable social and professional standing in America as keepers of the deep secrets of our minds. … New kinds of secrets about human mental life and its disorders were needed.

–Paul McHugh, MD, The Mind Has Mountains, p130

Dr. McHugh argues that the primary appeal of Freudism was never its explanatory power, but rather the sense that everything could be condensed to a simple narrative, as will as the feeling of superiority it gave therapists as holders of “secret” knowledge.

Oddly enough, Tim Keller once spoke about a similar trait in one of his sermons (I can’t find the specific quote), of people who become so enamored with their own particular take on the gospel that it becomes an idolatry all of its own. They’re not so convinced by the argument as they like having thought of it and they like it being theirs, and so it assumes an all-encompassing importance to them. They like, in short, the sense of superiority it gives them. One could even extend this judgment to scholars of obscure books or “super nerds” who viciously defend the hidden bits of obscure lore they know about Star Wars, or Star Trek.

Or heck, much as I love it, Lord of the Rings. I’ve written my own thoughts about Rings of Power, here, but it was absolutely astounding to me to go through reddit forums and view the absolute vitriol being thrown at the show for not having large enough ships, or having plot holes, or having disputable takes on obscure points of lore that Tolkien never clarified in his actual books. Posters were breathing fire over adaptational differences, and when you reminded them it was just a show, you’d get hit with “well, I guess I just love Tolkien’s world too much.”

But that’s not it. They love knowing minutae, arguing minutae. They love their own personal theory of Tolkien more for it being their theory far more than they love Tolkien himself. They love the feeling of knowing more than others, lording that knowledge over others. That is why no adaptation will ever please people like this, because the point is actually to not be satisfied, to demonstrate their superior knowledge/purity over other people.

You see this everywhere. You see this with people arguing sports trivia, science theory. You see it with pedagogy with “secret tricks” like learning styles. In many ways it springs from the very good impulse for learning and discovery–it wouldn’t be so strong if it didn’t. But then egomania hijacks it, as it does with so much, and our delight in our secret, hidden knowledge that others don’t have becomes more important than the pursuit of truth itself, and that makes the “secrets” unquestionable truth.

That’s why people will literally shoot up a pizza place than consider the notion that “government insider” leaking “intel” to them is just an online troll farming engagement. It’s why people will persist in believing that their billionaire real-estate mogul leader is a real “man of the people” rather than consider they’ve been conned. And, to return to a soapbox I’ve been on a lot recently, it’s why there are people getting trapped in personal delusional worlds as AI-companions programmed to be agreeable assure them that yes, they’ve absolutely stumbled onto proof of AI-super-sentience, how smart you are to have discovered this.

I’m struggling to bring this to a kind of moral. Ecclesiastes 12:12 seems relevant–a verse that always makes me chuckle, as a a former grad student: “Be warned, my son, of anything in addition to [the words of the wise]. Of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body.” Getting overly obsessed with commentators on commentators gets us nowhere. Obsessive study is not a worthwhile end in itself.

I’d also feel confident in saying that knowledge should never be about boosting your ego. It shouldn’t be about showing how smarter or more passionate or more gifted you are than others. Knowledge is meant to be put in conversation with other people, other bodies of knowledge, not kept secret and obscure, and the more specialized and divorced it is from other fields, the less likely it is to be true.

I think you are right on with your analysis that we all like to think we have a corner on information. Thanks for putting that into a framework so that we can understand ourselves better.

I also love hearing about your memories of the school and what you learned.

LOL– “the absolute vitriol being thrown at the show for not having large enough ships, or having plot holes, or having disputable takes on obscure points of lore that Tolkien never clarified in his actual books. Posters were breathing fire over adaptational differences,”

Well put!!

LikeLiked by 1 person