I used to teach American Lit. I’m going to again, actually, this coming year, but it has been a few years. One of the things that occurred to me when I last taught it. Part of the point of teaching American lit is to give kids a cohesive sense of culture. We study the seminal works written by Americans that express—and shape—what it is to be American. Not just classics like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, or the Puritans or such, but also indigenous legends and modern classics like (sigh) Catcher in the Rye.

Sometime I’m going to write an entire blog post about everything I hate about Catcher in the Rye. I mean, it might still be a great book, I just personally hate it.

A history prof of mine, by the name of Dr. Andrew Mitchell, once argued that American “culture” does not exist. Americans are not “nationalist,” he would say, they are “patriotic”, meaning that they care more about the democratic system of government than any poorly-defined sense of “American culture.” If you asked what a distinctly “American” cultural dish was, people might say hot dogs, hamburgers, or pizza. But all of these are obviously derived from other countries. Can we really say they’re “American?” What is American cultural “dress”? A cowboy outfit? Cowboys were originally Spanish, and the costume comes from them. Even horses were introduced to America.

Telling friends this theory, though, has led to them pointing out that BBQ is unique to America, and what Americans consider “spaghetti” is very different from Italian spaghetti. “Orange Chicken,” while considered a Chinese food, is actually an American innovation. Hamburgers were indeed originally German, but Americans made them cheap, universal, putting them at the level of everyone around the world to eat and enjoy, to the point where restaurants in Hamburg, Germany advertise burgers as “real American food.”

This is what makes America great. Diversity, and the can-do innovation that springs from that. Culturally, demographically, even geographically, America is defined by nothing more than its sheer diversity, the “melting pot” which takes ingredients from millions of cultures and subcultures, combines them all, and puts them out again with a new twist. America’s heritage is that of leaving your old world behind to join a new world full of strangers—while bringing a bit of your home there to change the new world.

America is a nation of differences, most visibly racially, but most prominently ideological. And this, I think, is the thing most distinctively American. Diversity, yes, but from that two more. Arguments. Dissatisfaction. We’re built from people dissatisfied with their homeland–even the original indigenous tribes came here from a land they presumably disliked. Our very electoral system is defined around ideas competing, coming together, and making strange combinations. The right to argue is firmly enshrined in the Constitution.

There is nothing more American, one could say, than hating America. Especially because most people who claim to hate America will usually immediately qualify that they love what America is “supposed” to be. They just disagree on what, exactly, that means.

And, honestly? I think that’s kind of great.

Seriously, it keeps us from settling. It keeps us from being satisfied with the status quo, from resting on our laurels, from just sitting back and being satisfied with things. Because being happy with the state of things is not American. Take that Zen stuff out to Tibet or maybe England to sip some tea. We do not sit still. The comedian Phil Jupitus has a bit about how of course America was the nation to go to the moon, because we’re all the mad lads who stormed across the ocean, then decided to go riding all over to the clear other side of the country, and after we got there essentially said “Ooh, look, the moon, let’s have a go, eh?”

(Again, if it sounds like I’m speaking exclusively of European settlers here, note that First Nation peoples were also likely formed of the tribes who decided to stom over land bridges or what not. And, also they spread out pretty well over the continent)

There’s more than a technological element to this. America’s cultural dissatisfaction actually does a remarkable job, I think, of keeping our country relatively honest.

Back when the immigrant camps were on everyone’s minds (i.e., when a Republican was in charge and the media was interested), people were (as people do) throwing around comparisons to the Nazis and concentration camps. There are many huge and significant distinctions, not least of which is the lack of a systematized murder plan. It is, also certainly, worth pointing out that the Nazis studied American Jim Crow laws and looked to American Native American reservations for parts of their system. (though again, “studied” is not the same as “copied.”) It’s also worth noting that German concentration camps were originally meant as prison camps swiftly beset with overcrowding and food shortages, which has… uncomfortable similarities with the immigrant camps, even now.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that anyone involved with the migrant camps had the slightest plan or desire to turn them into a death machine. There was rhetoric about the immigrants being an “invasion”, but even such alarmists never suggested the solution was to kill anyone, and any deaths resulting from people attempting to cross the border illegally were seen as tragedies.

But what occurred to me at the time was that even if anyone involved had had Nazi-like sympathies, it would have been very, very difficult to turn the camps into systematized death camps, by sheer virtue of the fact that so many people were watching and protesting already. The media had constant photographers around the camps, reporters asking questions. Senators were making speeches. Local churches were donating supplies–which guards had to throw away, because of regulations.

Of course, we changed presidents and the camps continue to operate, and the news media has suddenly become much less interested. But now the GOP has stepped in to scrutinize the same camps and deplore their inhumane conditions. And yes, this is hypocrisy on both sides, but it demonstrates an important point—the disagreeableness of Americans makes it very very hard for either side to get away with truly heinous acts.

WWII Polish farmers adjoining the Auschwitz camp knew exactly what was going on. They could see the smoke. They ignored it because there were stories the guards would shoot you if you approached the camp. Overcrowding in US migrant camps? People flip out. As they should; as is distinctly American.

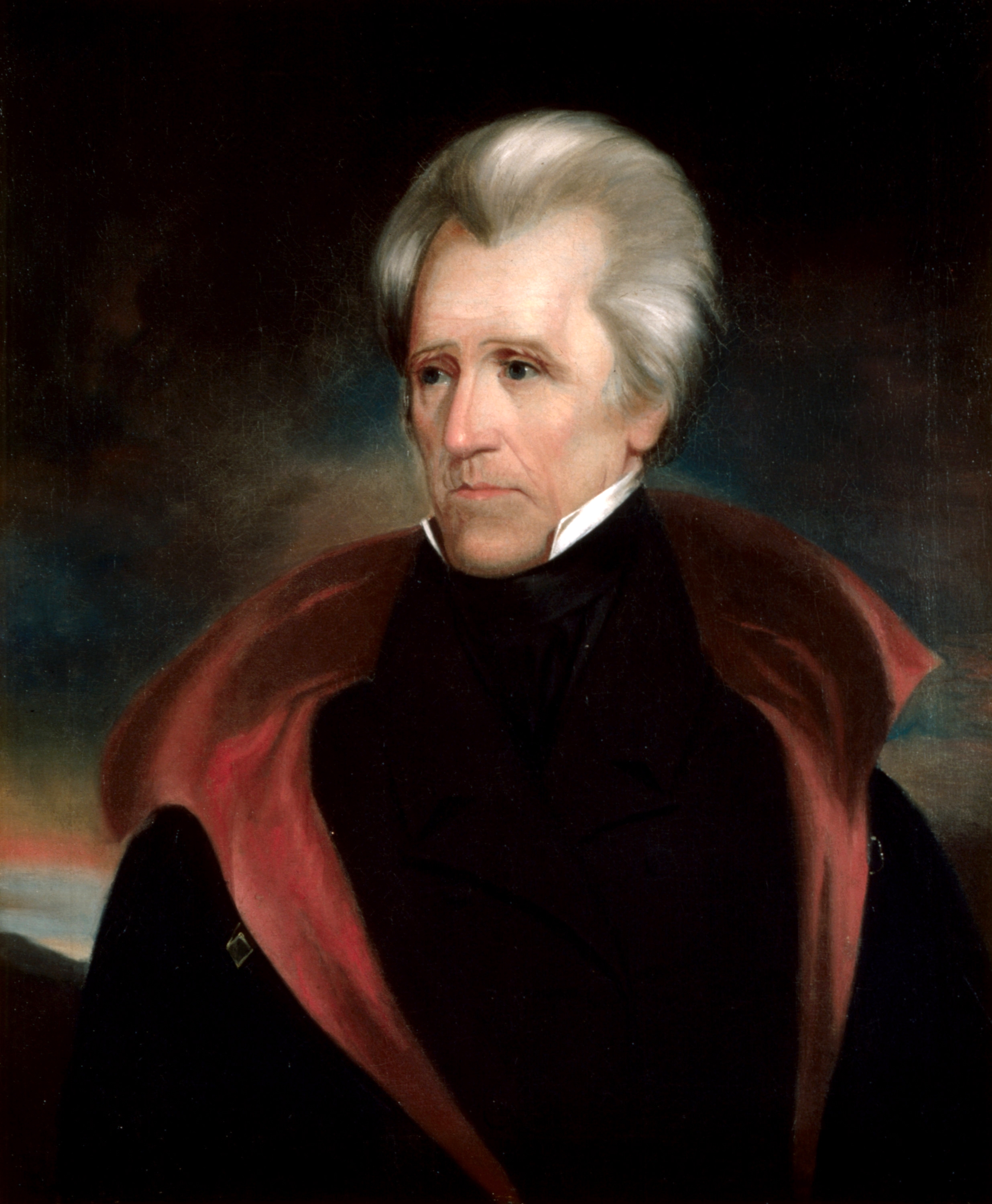

America has had some terrible mistakes in its past (which is why I’m annoyed whenever someone starts moaning about “the good old days”), but there were always sizeable groups of people against those mistakes. There’s less attention on it now, but there were strong protests over the Indian Removal Act, which barely passed Congress after fierce debate, and was actually declared illegal by SCOTUS (Jackson just ignored them.) Abolitionism dates back to America’s founding. It’s not necessarily because we’re more moral, we’re just more disagreeable.

Many other countries, actually, suffer from problems with police violence. The BLM protests (in the early phases) were echoed by similar anti-brutality protests around the world—sparked first by the American ones. Many other countries, as I’ve pointed out before, discriminate against races, creeds, and genders. France, which has the highest rate of police brutality, tried to make it a law to make it illegal to photograph officers. Check out the Canadian record against their indigenous population sometimes–or even the very real problems they still HAVE with racism, hoo boy.

But America is the one that struggles openly, in part because the many competing elements mean someone is always criticizing something. We’re dissatisfied. We complain. We argue–and when our worse natures get the better of us, sometimes we fight. No one, not even a conservative, is happy with the status quo.

On the other hand, many other countries just embrace the chaos of change, speeding ahead without asking whether where they’re going is somewhere they really want to be. The Netherlands and Belgium are just now starting to realize that assisted suicide can lead to some very not-good ideas in practice. And while other countries are culling Downs Syndrome children and rushing headlong into population-limiting strategies, China is currently providing a very large example of why that’s not a good idea. America is unable to settle for the status quo, but it’s unable also to ditch it entirely—because for everything one faction dislikes, another faction loves it deeply. We have a simultaneous impulse for change and for caution—or if you like, progression and conservation.

COVID, really, is an excellent example of how effective (and simultaneously unhelpful) American disagreements can be. The tension between the two parties kept the nation from entirely locking down, but also from entirely pretending it wasn’t there. We’re certainly not China, we’re certainly not Sweden. And we’re not Poland, either, which granted unlimited powers to its prime minister for an indeterminate period of time, an allowance guaranteed to corrupt even the most well-intentioned leader. A similar situation arose in Michigan through a legal loophole—and instead of people going along with it, there was massive backlash, pushing for a clear end. It would never have been practical for the Michigan governor to attempt to wield her powers for long, because the feuding parties made the political pressure too great. (though she tried).

Personally, I think America could have benefitted from adopting measures like masks and lockdowns earlier. Both would have been more helpful if the measures had been followed more uniformly. (this is the downside of American disagreements). But they weren’t helpful everywhere and in all circumstances, and the pushback against them helped them to be used in moderation, for the drawbacks to be constantly re-evaluated and measured.

The Expanse book Tiamat’s Wrath (and before that, Persepolis Rising) pictured this beautifully by showing the fundamentally flawed nature of a society that monolithically obeyed a single vision. Hero James Holden has a little speech.

“That’s the thing. The people you’re controlling don’t have a voice in how you control them. As long as everyone’s on the same page, things may be great, but when there’s a question, you win. Right?”

“There has to be a way to come to a final decision.”

“No, there doesn’t. Every time someone starts talking about final anythings in politics, that means the atrocities are warming up. Humanity has done amazing things by just muddling through, arguing and complaining and fighting and negotiating. It’s messy and undignified, but it’s when we’re at our best, because everyone gets to have a voice in it. Even if everyone else is trying to shout it down. Whenever there’s just one voice that matters, something terrible comes out of it.”

Persepolis Rising, SA Corey

I thought schools should stay closed. A lot of people thought so. A lot of other people disagreed. And because of that, school closings were not uniform across the nation, but varied according to severity (and to the amount of power teacher unions had in the state). And as it turned out, so long as you kept kids masked, opening schools did not create a disaster.

And at least part of that tug-pull relationship comes from America’s “melting pot.” How can America be satisfied with the status quo, when so many new people with new ideas are coming in daily? How can we rush on hastily to the newest trend, when so many of us are just getting our bearings in the new space? (contrary to expectation, Hispanic migrant populations are showing a decidedly conservative bent). How can the nation be uniformly agreed on ANYTHING, when so much of it is composed of so many different elements?

Which is, again, wonderful and frustrating.

Living in a diverse nation is not always so easy—again, differences lead to disagreements, and disagreements are not pleasant. Partisanship is one of the most insidious corruptions in politics today. Teaching, I can personally say, is really exhausting. There was a Harvard Business Review study of business environments which frankly found that people felt less comfortable working in a diverse environment. But. What it also found was that a diverse environment was overall more effective, more productive for the business itself.

To take this back to America, living in a nation that is diverse racially, culturally, religiously, ideologically can be difficult. It can be uncomfortable. It gets back to the subconscious aspect of racism I mentioned in my earlier blog. It takes you out of your comfort zone, it makes you self-conscious. But it is overall grander, spicier, richer for that discomfort. It takes Chinese food and makes it more Mexican–or say, it takes German hamburger steak and makes it more English. And somewhere in the middle, it becomes American.

America’s never been perfect. Frankly, I get irritated with people who whine about how terrible America is today for [x] or [y] reason, because I wonder when, exactly, they consider America was so unifyingly amazing. The 1990’s? 1960’s? 1920’s? America has always had issues, problems, evils to correct, and quite frankly some of the evils we USED to have were plenty horrifying. America (like every country) has always had problems, and one of the most American things to do has always been to complain about them. Ideally, also try to fix them–and frankly I think we’re pretty good at that too, though fair props to England for banning slavery long before we did.

But I don’t think we should let our national pastime of grumbling allow us to overlook that we do still live in a remarkable country. Dissatisfaction has definite benefits, but on its own its exhausting. America has had some really remarkable achievements. Be sure to think about those as well.

Essentially correct, I think. One of the big things that you see with the autocracies is that they’re fundamentally fragile, limited, uncomplicated. Putin didn’t have anyone willing to be a truth-teller about the state of the military. Xi’s diplomats get angry and lose their temper the moment anyone offers pushback. The attempts of OPEC countries to diversify away from oil are for the most part massive failures.

Competition breeds resilience, and while its exhausting, there’s never any doubt in the fighting spirit of the american.

LikeLike